The lore.kernel.org API

Written by David Tadokoro , published on September 4, 2023In my GSoC23 project, I had to understand the ins and outs of the lore API. By its API, I specifically mean the way requests to https://lore.kernel.org are responded, in other words, the syntax and semantics of requesting data stored in the lore archives, be it patches or available lists.

From the outset, the most critical point in my project was if the lore API provided

the necessary for kw patch-hub,

like I mentioned in my final report.

In this post, I’ll talk about what I discovered about the lore API and how we used it

in the development of kw patch-hub during my GSoC23 project.

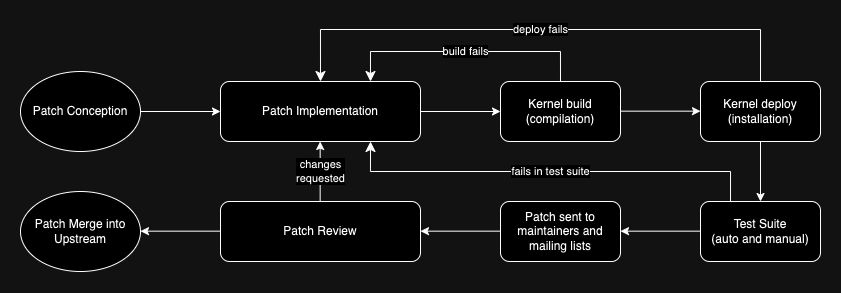

Linux kernel Contribution Model

When contributing to an Open-Source project, the contributor must first have a personal copy of the official project’s code. This “official project’s code” can be a git repository and this “personal copy” can be a fork of the former, for example. The second step is to find and make the desired change in the personal copy of the project’s code. Lastly, for the change to be incorporated into the project, in other words, to make it official, the change must be sent to the project’s maintainers for review.

Many projects fit this simplistic description of a contribution model. For instance, kw satisfies this model if we consider the official project’s code to be the official kw GitHub repository, my personal copy to be my GitHub fork of kw repository and the way of sending changes from my fork to the official repository to be Pull Requests.

The Linux kernel contribution model is similar to this, with the major difference of changes (named patches) being sent through public mailing lists. In general, Git is used for Source Code Management (SCM) in most Linux subsystems, but, unlike kw, changes aren’t sent upstream through Pull Requests, but rather as an email sent to a public mailing list (or lists) and the corresponding maintainers.

Below, is a diagram that illustrates this whole process from the conception of the patch, until its incorporation into the Linux kernel. This diagram, roughly, summarizes the life of a patch. The original diagram in Brazillian Portuguese was done by Rubens Gomes Neto for his capstone project.

The Classic Approach

As a maintainer, or just as someone who wants to help in reviewing, you would have to subscribe to the target list first to keep up with the patches (and discussions) sent to it.

Some problems may arise from this subscription approach, like having to keep a list of all subscribed emails sending individual copies to each one, and requiring the interested parties to be subscribed at all times, or else, some messages may be lost (this can occur even if the interested party is subscribed, though).

An On-Demand Approach

With the advent of the public-inbox technology,

which describes itself as an “archives first” approach to mailing lists, archives

of public mailing lists related to Linux kernel were created and hosted in

https://lore.kernel.org (for more information click here).

This alternate and complementary approach to consuming mailing lists relegates the need for subscriptions and all problems mentioned previously, and allows interested parties to adopt an “on-demand” approach to keep up-to-date. Besides this major benefit, some others can be listed, like allowing interested parties to consume lists using NNTP, Atom feeds, or HTML archives, and is easy to deploy and manage, facilitating mirroring.

Lore API

The API explained in this section is the result of much testing and experimenting with the lore archives. As there is no official documentation on it, some information may be imprecise.

For kw patch-hub, two types of data are requested to the lore

archives:

- Public mailing lists archived.

- Messages sent to an archived mailing list.

In this sense, requisitions for both types of data are responded to with a list of the

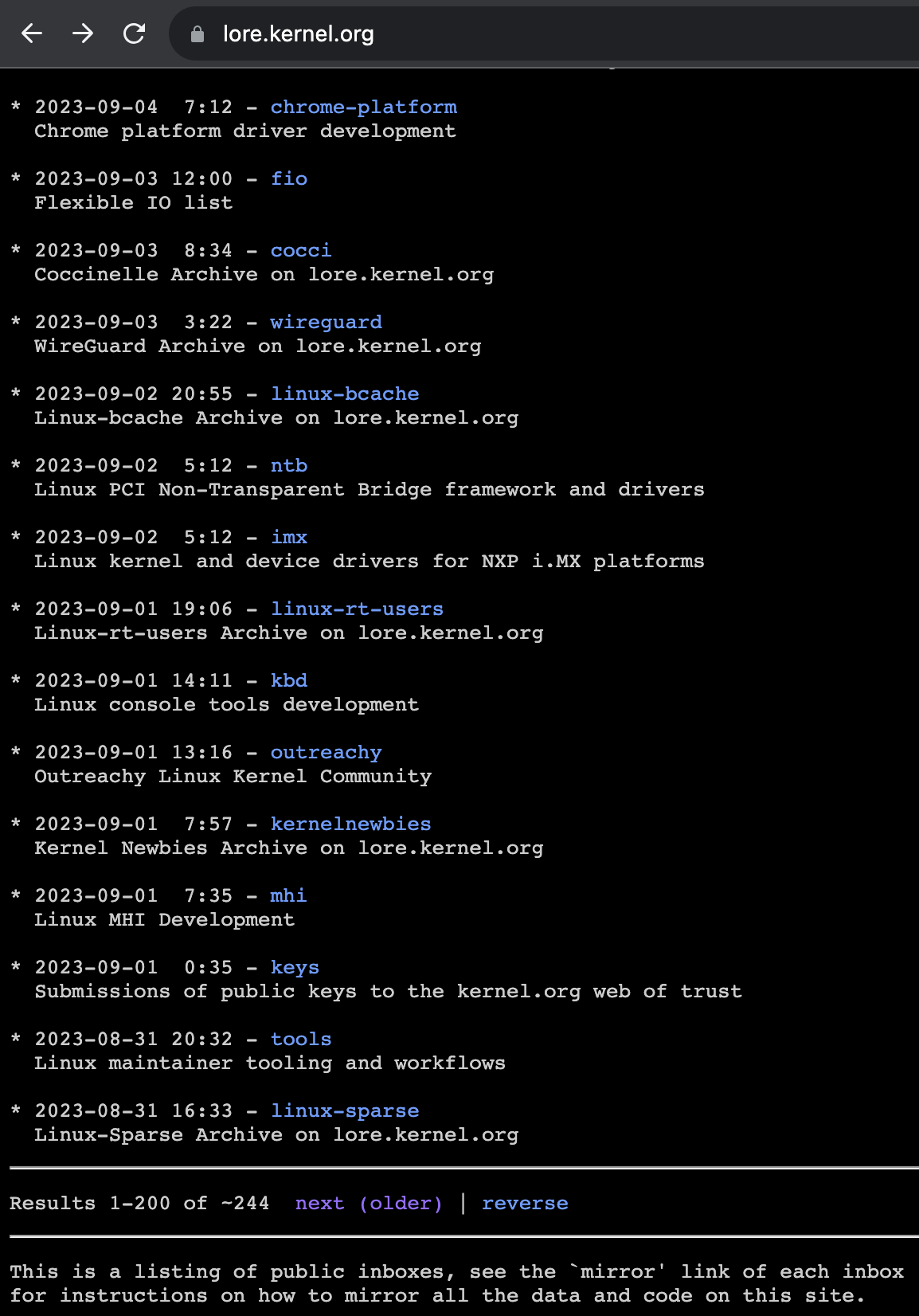

type of data. For example, by accessing https://lore.kernel.org in your browser,

the server responds with an HTML file with a list of the mailing lists archived.

If you access https://lore.kernel.org/amd-gfx a list of the latest messages sent

to the amd-gfx mailing list is received through an HTML file.

Query Strings

As with some other web applications, lore accepts the use of queries when requesting

data to get a more fine-grained result. These queries are added to a base URL

using Query Strings. In this string,

a query parameter is separated from its value by = (equal) and pairs of query

parameters and values are separated by & (ampersand). To give an example, a query

string that assigns cat to animal and yellow to color for the base URL

https://url.com/resource would be:

https://url.com/resource?animal=cat&color=yellow

Query Parameter o

In the lore API, an important query parameter is the o parameter. Most lore

responses are paginated as a means to not overflow the server with requests with

massive responses, say, one that the full response would be the whole history of

messages sent to a mailing list. Pages have 200 entries at maximum.

To illustrate, the screenshot below is the bottom of https://lore.kernel.org, which is a listing of the archived mailing lists, as said previously.

Notice the information Results 1-200 of ~244. It means that there are more than

200 mailing lists archived in lore and this HTML contains only the first 200.

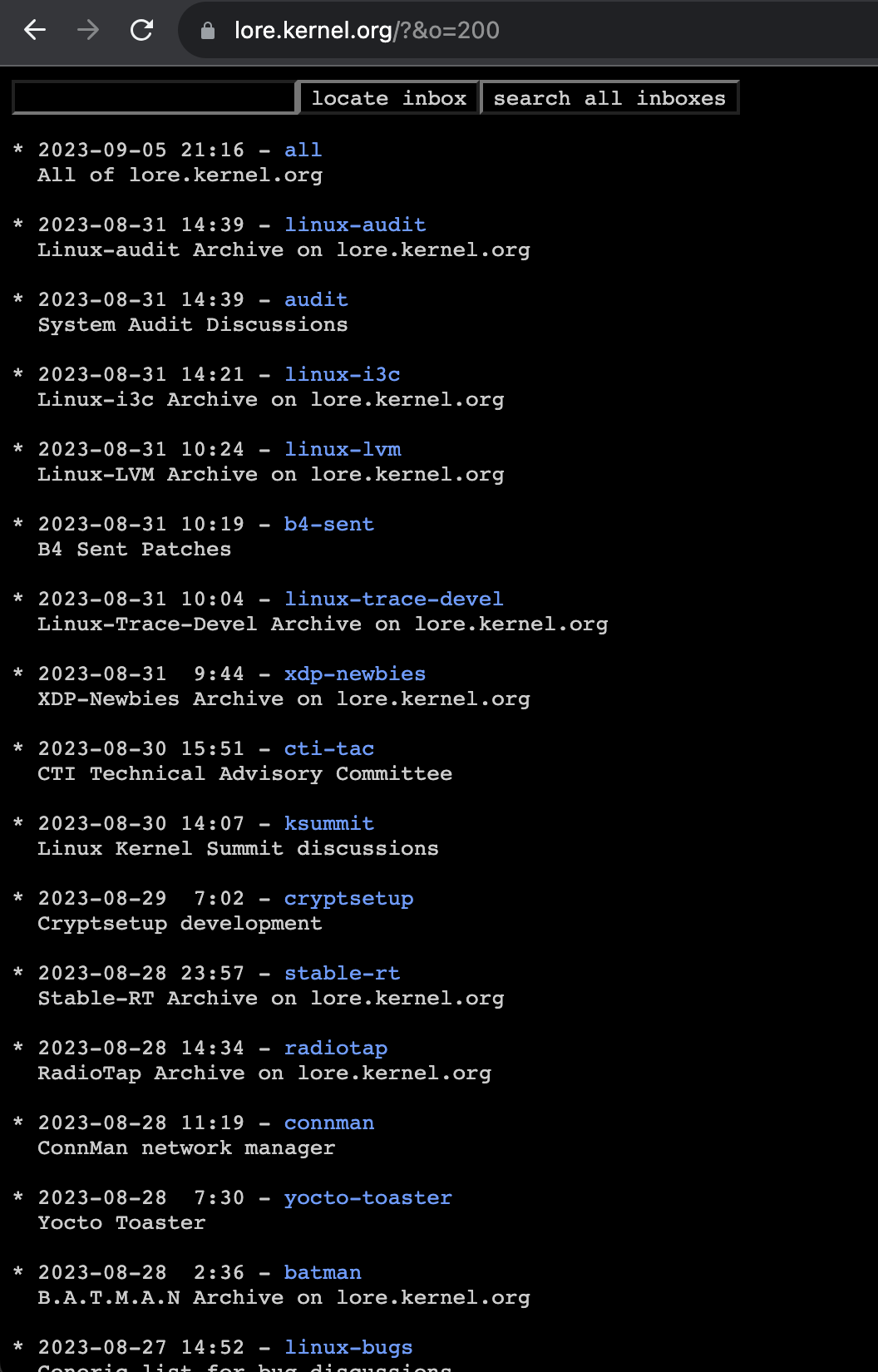

By clicking on the button next (older) we are redirected to https://lore.kernel.org/?o=200

that contains the remaining lists. The o=200 indicates that we want the archived

mailing lists from the number 201 onwards. The screenshot below is the HTML response.

This pagination mechanic also happens when requesting messages sent to a mailing list.

Query Parameter q

Another important parameter, that only applies for querying messages sent to a

mailing list is the q parameter. This parameter is complex and represents

a search for messages that fulfill some criteria. Lore has search functionality

provided by Xapian that supports typical operators AND, OR,

+ and - present in other search engines like google.com, and filters for matches

on specific fields of the message. Supported filters can be seen at

https://lore.kernel.org/amd-gfx/_/text/help (this is the help page related to

the amd-gfx list, but all lists support the same set of filters).

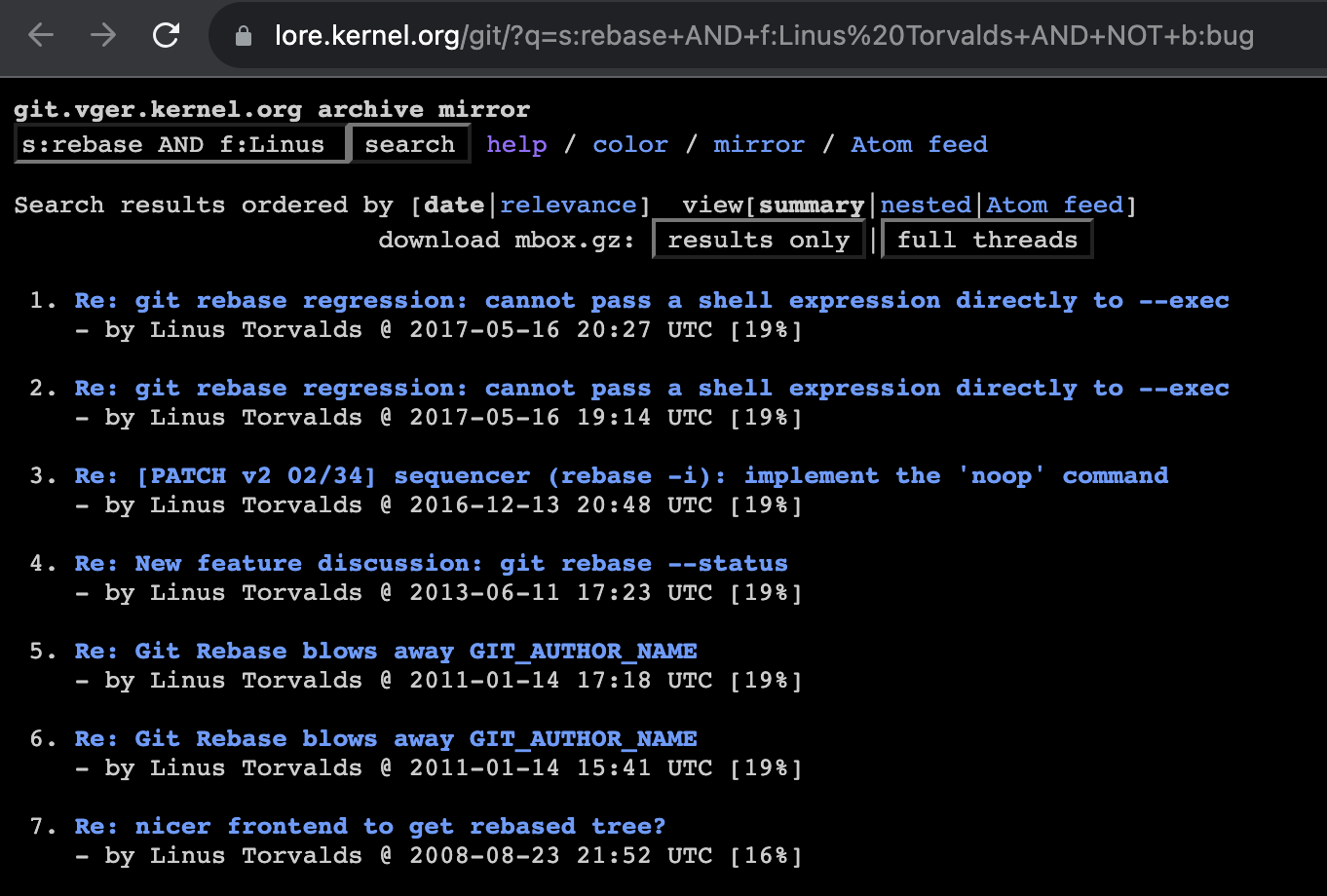

As an example, if we want to match messages sent to the git mailing list that

contain rebase in the subject, the URL would be

https://lore.kernel.org/git/?q=s:rebase

In this same example, if we wanted to match messages that contain rebase in the subject, were sent from Linus Torvalds and don’t contain bug in the message body, the URL would be

https://lore.kernel.org/git/?q=s:rebase+AND+f:Linus%20Torvalds+AND+NOT+b:bug

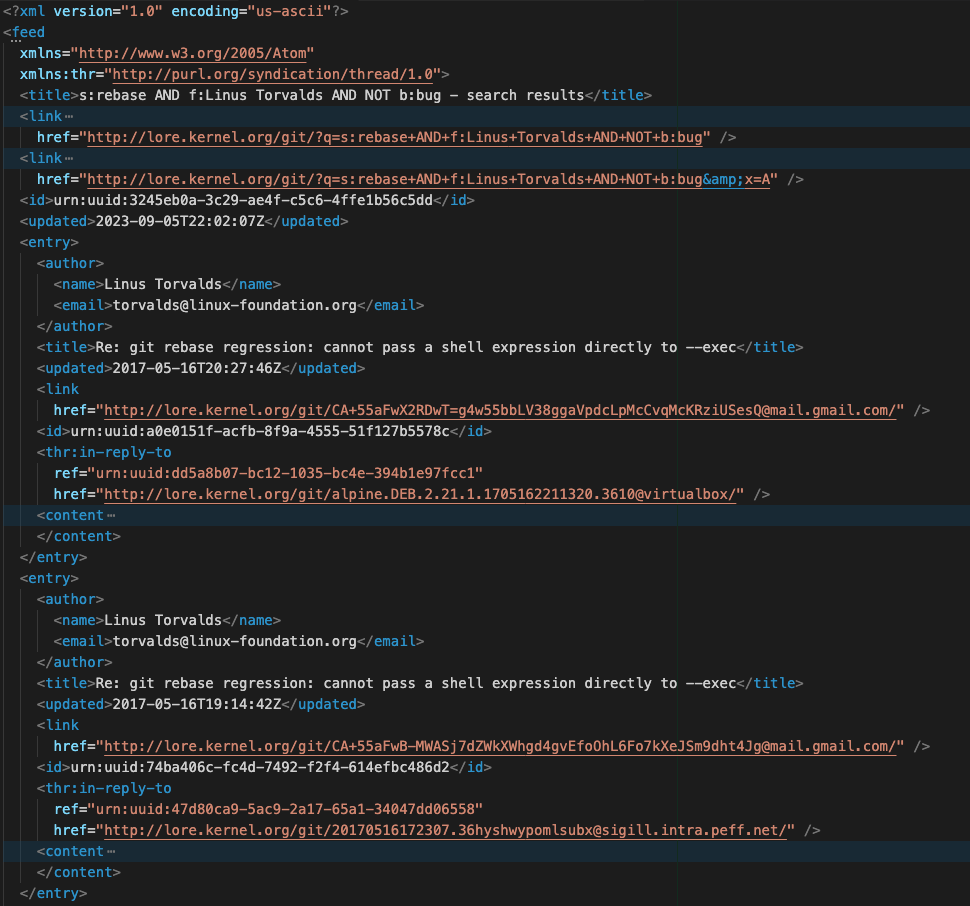

Query Parameter x

The last parameter that I will mention is the x parameter, which only applies to

querying messages and in conjunction with the q parameter. The only use that I

found for it is by setting its value to A, which makes the response of the request

to be an Atom feed. In essence,

this Atom feed is an XML file that follows the Atom Syndication Format

and has the same entries as an equivalent request that produces an HTML file, but

with different attributes for each entry.

Expanding further upon the last example, to get its Atom feed, we access the URL

https://lore.kernel.org/git/?q=s:rebase+AND+f:Linus%20Torvalds+AND+NOT+b:bug&x=A

The first screenshot below refers to the HTML file returned, while the second refers to the formatted Atom feed returned for the URL above.

Message-ID

Each message archived in lore has a unique identifier named Message-ID (the concept is discussed further here). An URL with the lore domain, an archived mailing list, and a Message-ID, uniquely identifies a message in lore.

As an example, the URL

https://lore.kernel.org/git/alpine.LFD.0.999.0708181547400.30176@woody.linux-foundation.org/

uniquely identifies the message sent by Linus Torvalds on August 18 2007 at

15:52:55 -0700 with the subject Take binary diffs into account for "git rebase"

to the git mailing list.

How kw patch-hub uses the lore API

As stated earlier, kw patch-hub has two tasks when it comes to consuming the

lore API directly: fetching the archived public mailing lists and fetching patches

(not any message) metadata from a given list.

Fetching Archived Public Mailing Lists

To fetch the archived lists in lore, we simply request the base lore URL https://lore.kernel.org, which returns us the first 200 mailing lists. Ideally, we would also need to fetch all the next pages (mailing lists from 201 onwards) to get all available mailing lists. This change is already cataloged and is due to be tackled soon.

It is worth noting that the “order” of lists returned from lore seems to be related to how active the lists are, but this isn’t confirmed.

Fetching Patches Metadata from a Mailing List

At the moment, every fetch of patch metadata has the same base structure:

https://lore.kernel.org/<target-mailing-list/?o=<min-index>&x=A&q=rt:..AND+NOT+s:Re:

<target-mailing-list> is the list to query for patches.

The o=<min-index> part of the query string defines the minimum (exclusive) index

of the patch on the response.

The x=A part of the query string is to obtain an Atom feed because it contains

metadata of the author name, author email, Message-ID, and, as the file is an XML,

we can use a tool like xpath to easily parse it for these desired fields.

The q=rt:..AND+NOT+s:Re: part of the query string is composed of two filters:

NOT+s:Re:: Thesprefix denotes the ‘subject’ of the message and theRe:means the literal string ‘Re:’. So, this filter translates to “match all messages that don’t have the literal ‘Re:’ in its subject”. This filter is really important since we are only looking for patches and they aren’t replies (i.e., don’t have the literal ‘Re:’ in its subject).rt:..: Thertprefix denotes the ‘received time’ of the message in lore servers, and the..means a period with both ends open, or, in other words, this filter can be translated to “match all messages that have any received time”. This filter is redundant, and the reason we used it is because lore API doesn’t seems to accept onlyq=NOT+s:Re:, so we apply a filter that in reality doesn’t filter anything.

In simple terms, the strategy to fetch patch metadata from lore is to manipulate

the o=<min-index> value to obtain adjacent chunks of patches. In reality, we

start with o=0 and add 200 for each consequent fetch. This allows kw patch-hub

to fetch data at the user’s desire (fetching more pages as he/she traverses through

the list history), while also respecting the 200 messages per response limitation

of the lore API.

Additional filters are appended to the end of this base structure, so, for instance,

if we want to request the third page of patches from the bpf list that have

the term ‘packet’ in its body, we use the URL

https://lore.kernel.org/bpf/?o=400&x=A&q=rt:..+AND+NOT+s:Re:+AND+b:packet

To better view the example above in the browser, remove

&x=Afrom the URL.

Conclusion

The kw patch-hub feature has some critical points in its implementation that rely

on directly consuming the lore.kernel.org API. Differently from other APIs, this one

isn’t well documented and much of the learnings expressed in this post were the

outcome of much experimentation, trial and error, and interpretation of what is

documented.

There are probably some other obscure intricacies of the lore API left to be discovered

that may help in improving kw patch-hub, but, in any case, the results achieved

at the moment validate the feasibility of the feature.